The Greatest Do Now Ever™️

This is the story of how one teacher set out to create the greatest Do Now Ever, and he changed my teaching for the better.

I looked up from my planning to a knock on my office door. It was Tom, another science teacher in the department.

“Adam,” he says, “can I run something by you?”

“Sure.”

I’ve known Tom since he joined us as an Early Career Teacher a couple of years ago. Tom’s smart, and really understands Teaching & Learning. His questions are always good.

“Don’t get cross with me.”

I raise an eyebrow, “why would I get cross with you?”

I don’t get cross with people. Certainly not Tom. Tom’s smart.

“I think,” he takes a breath, “I think our Do Nows aren’t good enough.”

I got cross.

Our Do Nows aren’t good enough!? Our Do Nows? Not good enough? Who the hell does this child think he is?? We spent years perfecting the routine! I co-founded an entire company dedicated to better Do Nows. I lead training on Do Nows. I wrote a blog a few years ago about Do Nows that has 14,000 views! This guy is cruising for a world of hurt if he thinks he can tell me our Do Nows aren’t good enough.

My eyes narrow, and I start parsing my fury…

“Hang on, just hear me out…”

I heard him out, and he was right. It took me a while to accept it, but Tom’s smart. He really understands good T&L. And he’s managed to build what I think is The Greatest Do Now Ever™️.

Tom’s objection was simple. As a department, we had a strong policy for long-term memory and retrieval over time. It involved students using Carousel Learning flashcards and then completing a free-response quiz. They self-assess their quiz, and we would moderate their assessments. A typical student would be answering hundreds of questions a year at home, and we buttressed that with Whiteboard quizzes in class (another ~8 questions per lesson) and feedback based on what we saw in their homework.

The overarching purpose of this was to give students lots of the right questions, lots of times. Carousel’s C-Scores helped us space the questions appropriately and ensure that tougher questions were revisited more frequently. Across the course of a year, we would expect students to be answering over 2000 questions between the flashcards, homeworks and Whiteboard quizzes. That’s a lot of questions, and we had evidence that this quality retrieval was resulting in improved outcomes.

Relying on students working at home is, however, a risky business. Even once students are in good habits around completing the homework, we can always question whether they have actually learnt anything from the homework.

Homework is traditionally completed as quickly as possible with minimal cognitive effort. There are lots of reasons for this, but many of them stem from a lack of perceived value in the homework. Students normally don’t value homework, and therefore don’t take it seriously.

Sadly, the teachers setting the homework often add to this valuelessness by setting homework as an afterthought, not checking it properly and not using it to inform planning. As I’ve written before, if we don’t value the homework, we can’t expect students to.

We tried to combat this through various formal and informal mechanics (check out Carousel’s book Retrieving Better for more on these), but - and this is where we return to Tom - those mechanics were never quite sufficient, and some students still weren’t taking their homework seriously enough. They were doing the homework, but not enough of them were learning from it.

In light of these imperfections, Tom developed a new system, complex in thought, but simple in execution. The best way to explain it is through the eyes of a typical student, in this case, Simon.

Simon’s science lesson is about to finish. His teacher Miss Mincer says “ok, pens down, eyes up here. Now you all know the rules - the second I see a student packing up, I’ll stop talking…” Simon sees Miss Mincer looking around the room. “Thanks everyone. I’ve put your quizzes online like usual. Lots of you really impressed me today, so I’m looking forward to seeing how well you do in the next one. You can pack up now, please.”

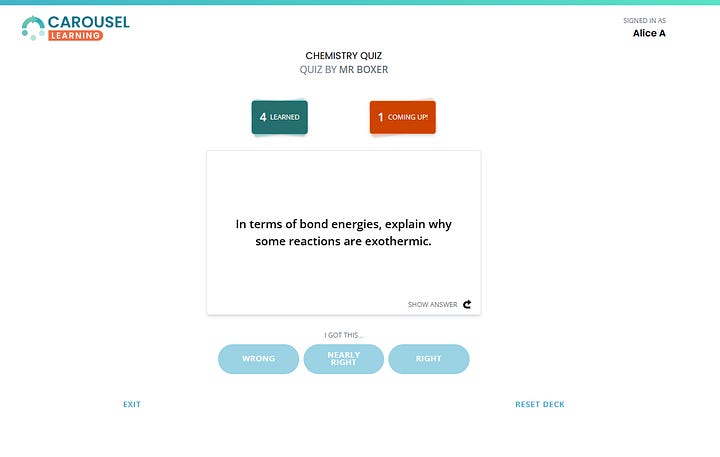

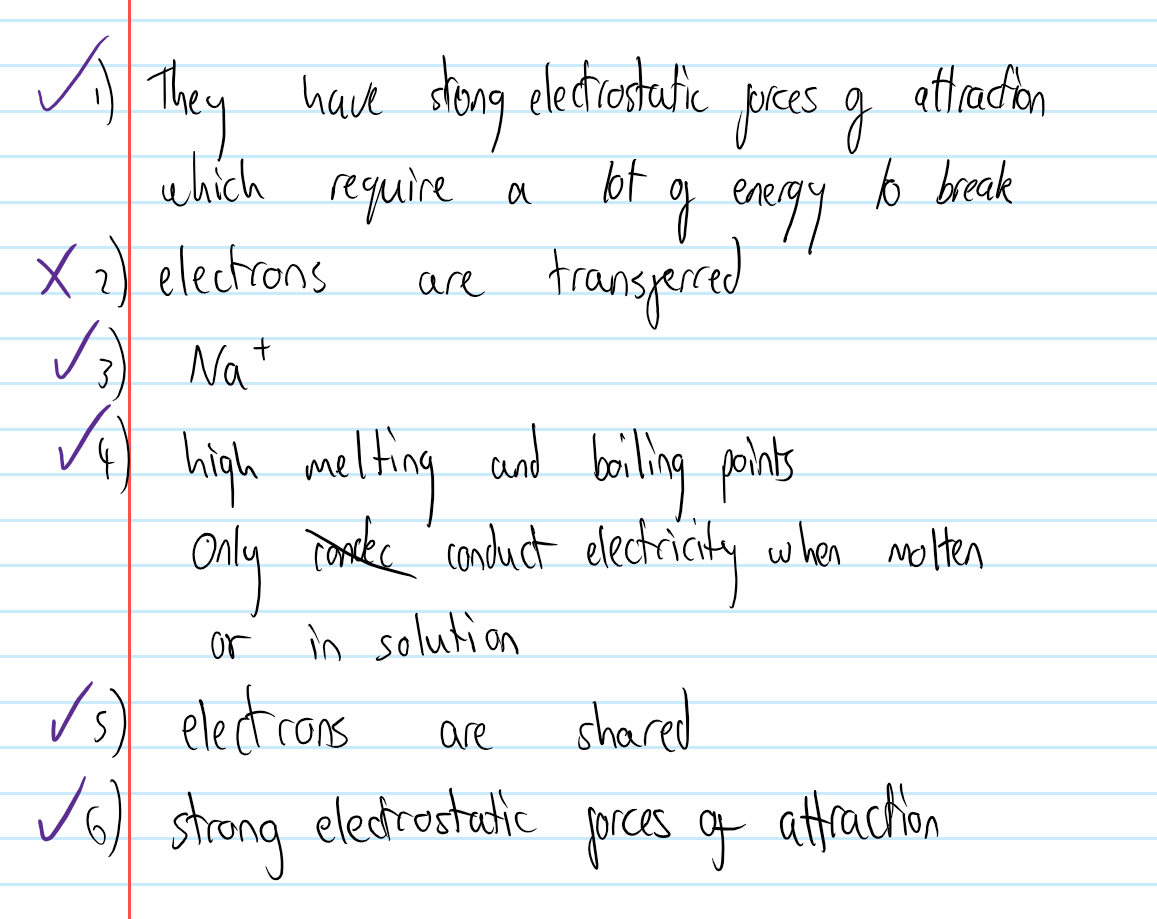

A few days later, Simon logs on to Carousel to do his homework. He takes out his exercise book and turns to the back. He opens up the flashcards, and reads the first one. He writes the answer in his exercise book, flips the card, and sees he got it right. He ticks it in his book, and clicks “RIGHT” in Carousel. This card will be removed from the deck.

He moves on to the next one, and again writes down his answer. He flips the card, but sees he got it wrong in his written answer, so marks it with a cross in his exercise book, and clicks “WRONG” in Carousel. He does the next card (right) and the next (right) and then the one he got wrong appears again. He gets it right this time, so ticks it, and clicks “RIGHT” in Carousel.

Eventually, there are no flashcards left in the deck. There were 20 flashcards to learn, so by the time he is finished, there are 20 ticks in his book.

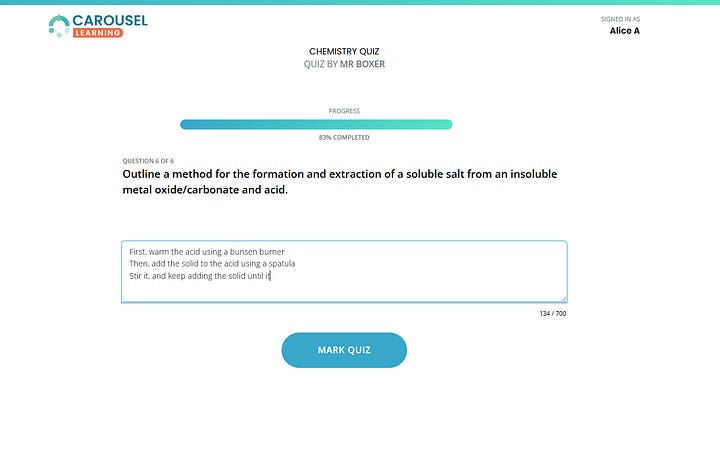

He closes the flashcards and his book, then completes and self-assesses his quiz.

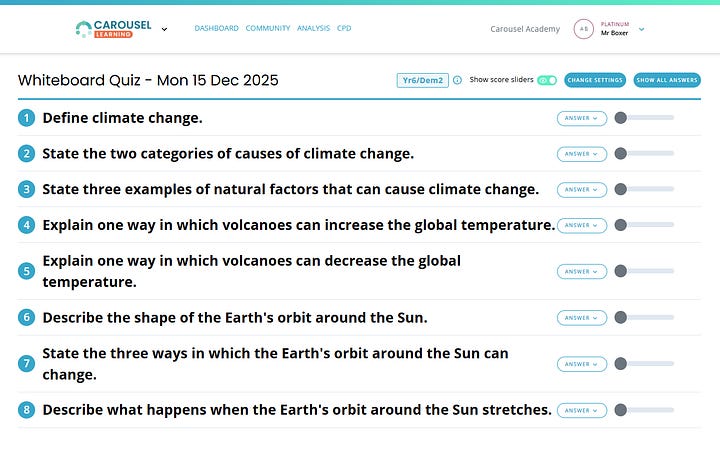

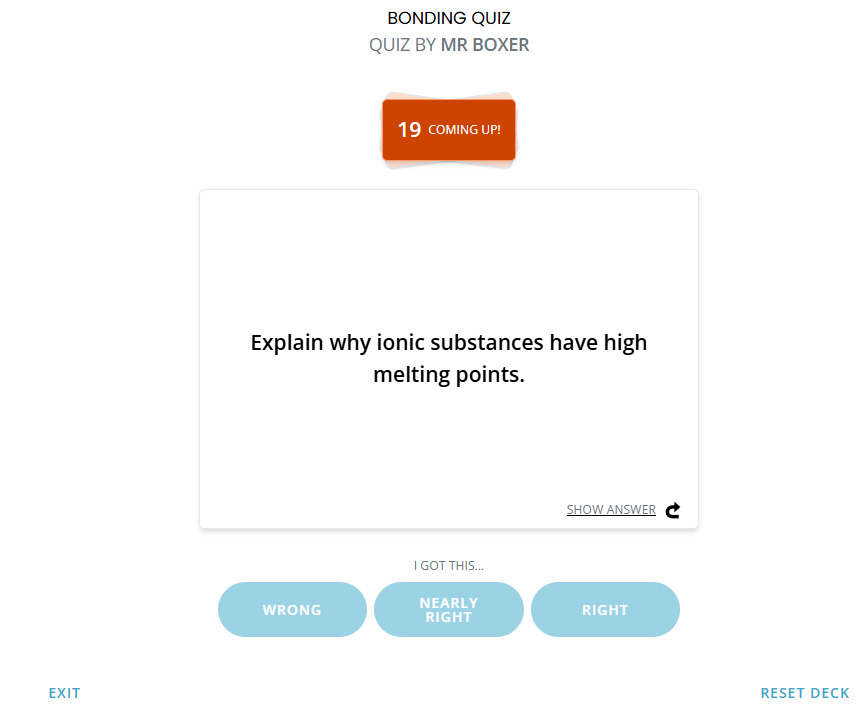

On the day the homework is due, he comes into the classroom. On his desk is a sheet of paper numbered 1 to 8, and there are 8 questions on the board. The questions are taken directly from the homework. He doesn’t write a title or LO or anything like that, he just cracks on with the quiz as quickly as he can. Just as he’s finishing the teacher says “thanks everyone, eyes up here…great…swap quizzes please…and hold up a purple pen in 3, 2, 1,...fabulous thank you…ok write your name at the top of the quiz so I can see who marked it…”

The teacher works through the questions, asking students for answers, and occasionally adding detail or emphasising specific marking points. She puts the answers on the board as she goes, which Simon finds helpful in marking. Simon is marking Clea’s test, and at the end of the marking he puts a score on her test paper - she got 5. Simon got 7. The teacher has a routine for getting the papers back, and within about 20 seconds there’s a neat stack on her desk. She says:

“Ok guys, as you know, I’m going to go through and check for who hasn’t made the passmark. If I call your name, at the end of the lesson you just head out to break. If I don’t call your name, make sure you stay so I can look at your flashcards. Amazing work David, well done Rama, fantastic Faduma…”

Simon hears his name called out, but he knows that Clea’s won’t be. The passmark is 6, so at the end of the lesson Clea will have to stay. The lesson progresses as normal, and Simon heads out to break.

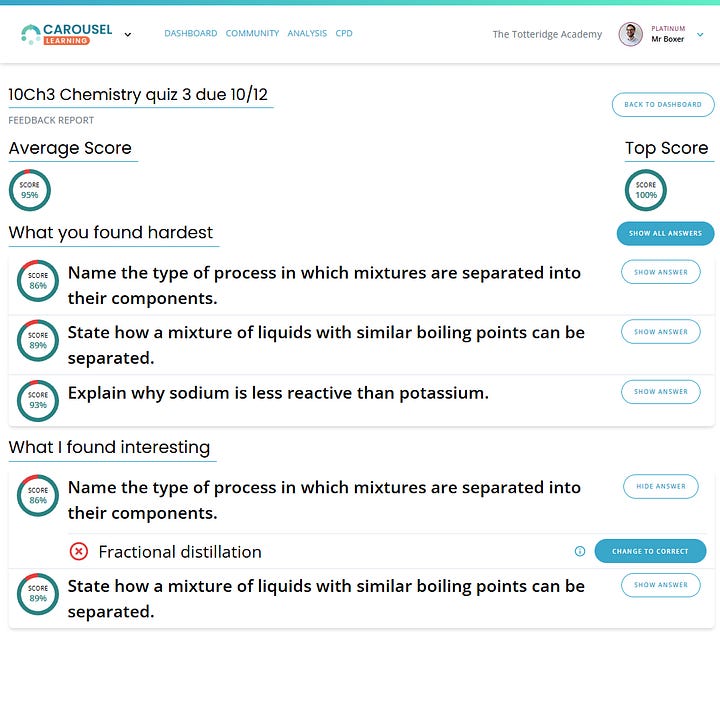

Clea stays in the room. The teacher is there with two students. She asks to see their exercise books, and looks in the back at the flashcards. Clea’s done the flashcards, and to a good standard, so Miss Mincer asks what went wrong. Clea explains that she confused ionic and covalent bonding in the quiz. The teacher asks a quick follow up question to check the confusion is gone for the minute, which Clea gets right. She says good job, marks a “y” in her spreadsheet and Clea heads off to break. Julie is left in the classroom, and she hasn’t done the flashcards. The teacher expresses her disappointment, marks an “n” in her spreadsheet and sets Julie a centralised detention, where she will go back and do this homework again. Julie goes to break, and Miss Mincer closes the spreadsheet - she doesn’t need to put in anything for the students who made the passmark.

The benefits of the system are clear:

Quality retrieval, every time: teachers know that students are answering lots of the right questions, lots of times. Because students are held to account for their performance in a subsequent quiz, they are incentivised to take the retrieval seriously.

Cheating is a thing of the past: in the digital age, students have the ability to cheat on any homework. They could take photos of the flashcards, use Google, or ask an AI. But regardless of whether or not a teacher can spot cheating at home, students definitely can’t cheat on the Do Now in class. Because of the triangulation between online quiz, flashcards in exercise books and score on Do Now, I can’t remember the last time I was worried that a student was cheating on their homework.

Interventions with students that need it: in the past, when a student wasn’t performing to their potential, I would have to start the conversation by scoping the kind of work they were doing at home, and trying to get them into better habits. Now, I can see exactly what they are doing at home, and if a student is doing the flashcards but still not hitting the passmark, it’s much quicker and easier for me to figure out where they need more help.

Student motivation: the homeworks we set have a wide range of customisable features (e.g., the difficulty of the questions, the number of questions, the number of retakes in the quiz). This means that teachers can tailor difficulty to their classes, resulting in every student in every class being able to meet and exceed the passmark. Some students sadly don’t often get the chance to succeed (especially when it comes to long-term learning), but in this case, the very structure of the task sets students up for success (see recent blog by Matt Evans and Becky Allen for more on the effect of tests on student motivation).

We didn’t switch to a new policy overnight. Tom trialled and refined his idea across two terms before rolling it out. He asked other members of the department to try it out. He took their feedback, and iterated the process. He carefully scrutinised any workload implications, and built the tracking sheets to be as quick and easy as possible. He (and the HoD) worked hard to make sure that the centralised detention system was efficient and effective. He built training materials for students and showed the department how to model the new system to students and set expectations. He filmed colleagues doing it so we could discuss as a group and improve our own delivery. He wrote guides for parents which were sent home en masse. He not only invented a brilliant new routine, but he rolled it out masterfully. Leaders everywhere take note.

Tom even managed to convince cantankerous old grumps like me. One of our school’s mottos is “we never arrive,” and he challenged me to realise that I hadn’t arrived, and my practice could improve. Less than a term in, I’m already seeing those improvements. I set my Key Stage 4 classes around 40 questions each homework. I actually now quiz them on 10 of those questions, and set the pass mark at 8. Without fail, the overwhelming majority of students can answer them without hesitation, and I tend to have only one or two students per week (if any) failing to meet the passmark.

We still have some iterations to come - after all, we never arrive. For example, I’m worried about last-minute cramming distorting the long-term effects of retrieval, so I’m working on ways to interleave in questions from old quizzes as well. But the early signs are extremely promising, and until someone shows me a better one, I’m pretty sure this is The Greatest Do Now Ever™️.

My thanks go to Tom Mourant and the entire science department at The Totteridge Academy for their innovation, collaboration and readiness to try new ideas. My thanks as ever to Thanos Gidaropoulos, whose views and strategies around student accountability are the intellectual origins of The Greatest Do Now Ever™️.

Everything in this blog is made possible by having access to Carousel Learning. To learn more and book a demo, click here. We are also aiming to film one of these lesson starts in January to go on the Carousel Teaching platform, so to keep up to date, make sure to subscribe to stay updated!

which aspects of this strategy do you think teachers can learn from in schools which can’t or won’t fund carousel learning?